Figure 12A.1 Pipeline

Alignment and Trench Type

|

|

Figure 12A.2 Pipeline

Trench Types

|

|

This

Annex covers details of the

Quantitative Risk Assessment (QRA) for the two subsea pipelines from the

Mainland China to Black Point Power Station.

Details of the methodology are presented here whilst the results and

conclusions are given in Section 12 of the EIA Report.

Two

20 km pipelines are proposed, although and only 5 km of the pipeline alignment

lies within Hong Kong SAR waters. It is

this 5 km of pipelines that are the subject of this analysis.

The

first pipeline will likely be completed towards the end of 2011 and so the

assessment considers the population in this year as the base case. Construction of the second pipeline will

likely take place in 2014. A future

scenario is also considered for the year 2021 when both pipelines will be

operational.

12A.2

Data Collection

& Review

The

proposed pipelines from the Mainland China to Black Point are in many ways

similar to the subsea pipeline that was proposed as part of the LNG terminal

project for

·

Project

Profile, ERM [1];

·

Drawing

HKLNG-WPL-00-PIIP-PL-009 detailing the pipeline trenching and backfill details,

Worley Parsons [2];

·

Marine

vessel density data, BMT [3];

·

Marine

traffic data in

·

·

Hydrographic & Geophysical Survey of the Seabed,

EGS [7]; and

·

Environmental

and Risk Assessment Study for a LNG Terminal in

This section of the report describes the subsea

pipelines, their environment and details of marine traffic along the proposed

route.

The proposed pipelines take a subsea route from the

Mainland China to Black Point Power Station.

The pipelines will cross the

Details of the pipeline are preliminary at the time

of writing but will likely consist of two pipes of between 32” and 42”

diameter. These will be located in

separate trenches constructed about 2 years apart. These differences are not expected to make

significant differences in the risk results but where there is uncertainty in

the design, the analysis has made assumptions that err on the conservative side. For example, the larger diameter of 42” has

been assumed in the analysis since this creates a larger gas inventory. Construction of the pipelines at different

times has also been considered.

The operational pressure within the pipelines is

expected to be 63 barg, however, the maximum operating pressure of 100 barg (design pressure) is used in the analysis, again as a

conservative upper limit. The pipelines

will have an anti-corrosion coating and sacrificial anodes for external

corrosion protection and an outer layer of reinforced concrete for buoyancy

control and to provide mechanical protection during pipeline installation and

trenching operations. A summary of the

pipeline details is given in Table 12A.1.

The composition of the gas is mainly methane (85-99.5

mol%) and is such that no internal corrosion is

expected.

The pipelines will be buried below the seabed with

varying levels of rock armour protection (Figures

12A.1 and 12A.2). Type 1 trenching will be used for the

approach to Black Point. The type 1

trench involves dredging with 1.5m of rock armour backfill (measured from the

top of the pipeline). This provides

protection for anchors up to 3 tonnes, essentially protecting against anchors

from all ships below about 10,000 dwt.

Trench type 2 is used in shallow water areas away from the busy marine

fairways. Type 2 consists of

post-trenching with about 5 m of armour rock and natural backfill. This is designed for protection from 3 - 5

tonne anchors (i.e. from all ships below about 10,000 dwt) and any future

dredging work.

Table 12A.1 Summary

of Pipeline Details

|

Parameter |

Details |

|

Location Length Outside diameter Nominal wall thickness Line pipe grade External coating Cathodic

protection Design flowrate Design pressure Delivery pressure Maximum delivery pressure Pressure assumed for analysis Operating temperature Water depth Seabed soil Pipeline protection Design life |

Mainland to Black Point Power Station 20 km 42” 1” API 5L X70 anti-corrosion coating Aluminium based sacrificial anodes 1200 MSCFD 100 barg 63 barg 100 barg 100 barg 12 °C 2 – 20 m Very soft clay becoming firmer with depth Up to 3m cover with rock armour backfill 25 years |

The busy

Figure 12A.1 Pipeline

Alignment and Trench Type

|

|

Figure 12A.2 Pipeline

Trench Types

|

|

12A.3.2

Marine Traffic

The marine traffic influences the risks from the

pipeline in two ways:

·

It

increases the potential for damage due to interference such as anchor drop/drag

incidents; and

·

In the

event of a pipeline failure, marine traffic could exacerbate the consequential

effects causing fatalities.

The marine vessel traffic volume was surveyed by BMT

[3] using tracks of vessel movements obtained from radar (Figure 12A.3). Details from the BMT report that are

pertinent to the current study are summarised below.

Marine Vessel Activity along

The marine traffic report [3] divided the previous

South Soko to Black Point pipeline route into sections

using ‘gate posts’ that roughly corresponded to key locations along the

alignment. Three of these gate posts

remain applicable to the current study and were used to estimate marine traffic

crossing the 5 km of pipeline within Hong Kong SAR waters (Figure 12A.3).

Figure 12A.3 Radar

Tracks of Marine Traffic

|

|

The section between gates 1 and 2 is used by fishing

vessels and some rivertrade vessels en route between Tuen Mun and Zhuhai. The water is shallow in this region, ranging

from 2 - 5 m deep. This precludes its

use by large draft vessels.

Gate posts 0 and 1 span

Vessel Types

The marine traffic consultant calculated the marine

traffic volume between pairs of gate posts based on radar tracks [3]. The vessel speeds and apparent size from the

radar returns are interpreted into 6 marine vessel categories (Table 12A.2). The same categories are used for the current

study.

Table 12A.2 Vessel

Classes Adopted for Assessment

|

|

Based on this vessel classification, the population used

in this study are as given in Table 12A.3. The maximum population of fast ferries is

assumed to be 450, based on the maximum capacity of the largest ferries

operating in the area. However, the

average load factor of ferries to

Table 12A.3 Vessel

Population

|

Class |

Population |

|

|

|

Fishing vessels Rivertrade

coastal vessels Ocean-going vessels Fast launches Fast ferries Others |

5 5 21 5 450 (largest ferries in peak hours, 4

hours a day) 350 (average ferry in peak hours, 4 hours

a day) 280 (80% capacity, peak hours, 4 hours a day) 175 (50% capacity, daytime operation, 9

hours a day) 105 (30% capacity, late evening, 4 hours

a day) 35 (10% capacity, night time, 7 hours a

day) 5 |

3.75% of trips 3.75% of trips 22.5% of trips 52.5% of trips 12.5% of trips 5% of trips |

|

Traffic Volume

The traffic volume as provided by BMT [3] is given in

Table 12A.4. This is based on radar tracks for the year

2003. The current study takes year 2011

as the base case since this is the expected year of completion of the pipeline. A future case, year 2021, is also

considered. BMT provided predictions for

the traffic increase to years 2011 and 2021 (Table 12A.5). The traffic

growth rates presented in Table 12A.5 do not take into account the

development of the Tonggu Waterway which has been

implemented recently. This is expected

to shift ocean-going vessels away from

The data in Table

12A.4 required further interpretation.

Vessel class A2 is described as fast launches and fast ferries. The population of a fast launch is very

different from that of a fast ferry and so a more precise breakdown is

required. Some of these A2 fast ferries

clearly belong in class B2 with the other fast ferries. Taking into consideration the timetable of

ferries serving the

Class C2 is described as fast ferries and ocean-going

vessels. Since all fast ferries have now

been accounted for, class C2 are assumed to comprise of cargo ships only.

The data shows a small number of ocean-going vessels

(class C1 and C2) along the route between gates 1 and 2. The shallow water along this section negates

the possibility that these are large vessels.

They must be vessels at the smallest end of the distribution of

ocean-going vessels, no more than 100m long [10]. More likely, they are rivertrade

vessels. They were therefore treated as

smaller vessels in the analysis by reclassifying them as either rivertrade or ‘other’ vessels.

Table 12A.4 Traffic

Volume across Gate Sections (Daily Average, 2003)

|

Vessel Class |

Total |

||||||||

|

Vessel

Speed (m/s) |

0-5 |

5-25 |

Others |

||||||

|

|

0-30 |

30-75 |

75+ |

0-30 |

30-75 |

75+ |

|||

|

From Gate |

To Gate |

“A1”

Fishing Vessels and Small Craft |

“B1”

Rivertrade Coastal Vessels |

“C1”

Ocean-going Vessels |

“A2”

Fast Launches and Fast Ferries |

“B2”

Fast Ferries |

“C2”

Fast Ferries & Ocean-going Vessels |

||

|

0 |

1 |

250 |

265 |

45 |

150 |

110 |

40 |

5 |

865 |

|

1 |

2 |

40 |

5 |

1 |

50 |

50 |

5 |

10 |

161 |

Notes: Values

>5 are rounded to nearest 5

Daily

values based on 9 day record. Some

rounding applies

Table 12A.5 Traffic

Growth Forecast

|

Vessel

Type |

2011 compared to 2003 |

2021 compared to 2003 |

|

Ocean-going Vessel* Rivertrade

Coastal Vessel Fast Ferry Fishing Vessel/ Small Craft/ Fast launch Others |

-5% +5% +10% +5% +5% |

+10% +15% +30% +15% +15% |

* The traffic growth forecasts for 2011 and 2021 do

not take into account the development of the Tonggu

Waterway. This waterway is expected to

shift ocean-going vessels away from

12A.3.3

Sectionalisation of the Pipeline

Based on the above discussions and the level of

pipeline protection, the pipeline route was divided into 4 sections for

analysis (Table 12A.6). The four sections include:

·

Black

Point Approach - the 0.1 km shoreline approach to BBPS;

·

Black

Point West - the shallow water section between Black Point and

·

·

Boundary

Section - the shallow water section between

Given that the pipeline sections do not correspond

exactly with the gate posts used for determining the marine traffic,

redistribution of the marine data was required.

With insight gained from the radar tracks, knowledge of water depth and

ferry activities, the following assumptions were made:

·

95%

of the marine traffic between gates 0 and 1 is assumed to pass through

·

The

remaining 5% of traffic observed between gates 0 and 1 are assigned to the

Black Point West section. These marine

vessels are assumed to be rivertrade vessels, fast

launches, ferries and fishing boats. No

large ocean-going vessels are expected here due to the shallow water;

·

Although

no radar tracks are observed within the 100m shore approach, a small number of

small crafts are assigned to this section as a conservative measure;

·

The

mix of vessels observed between gates 1 and 2 is assumed to be representative

of vessels crossing the Boundary Section of the pipeline. Half of the traffic observed between gates 1

and 2 is assumed to traverse the Boundary Section of pipeline.

Table 12A.6 Pipeline

Segmentation

|

|

Section |

Kilometre Post |

Length (km) |

Typ. Water depth (m) |

Trench type |

|

|

From |

To |

|||||

|

4 |

Boundary Section |

0 |

0.73 |

0.73 |

2-20 |

2 |

|

3 |

|

0.73 |

2.52 |

1.79 |

20 |

3 |

|

2 |

Black Point West |

2.52 |

4.78 |

2.26 |

5 |

2 |

|

1 |

Black Point Approach |

4.78 |

4.89 |

0.11 |

2 |

1 |

Based on the above assumptions, the marine traffic

volume used in the present analysis is summarized in Table 12A.7.

Table 12A.7 Traffic

Volume Assumed for Base Case 2011

|

|

Traffic volume (ships per day) |

|

|||||||

|

Section |

Fishing |

River-trade |

Ocean-going |

Fast Launch |

Fast ferry |

Other |

Total |

||

|

4 |

Boundary Section |

21 |

3 |

0 |

24 |

30 |

8 |

86 |

|

|

3 |

|

250 |

265 |

81 |

118 |

150 |

5 |

869 |

|

|

2 |

Black Point West |

12 |

16 |

0 |

5 |

8 |

2 |

43 |

|

|

1 |

Black Point Approach |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

|

|

|

Total |

284 |

284 |

81 |

147 |

188 |

15 |

999 |

|

Tables of traffic

volume for the 2021 future scenario were created in a similar manner. This is given in Annex 12 of the EIA Report.

Ocean-Going Vessel Distribution

All classes of ship, with the exception of ocean-going

vessels, have anchor sizes below 2 tonnes (Table

12A.2), and it is noted that the entire length of the proposed pipeline

will have rock armour protection designed to protect against at least 3 tonne

anchors. Ocean-going vessels cover a

very wide range of size. A breakdown of

the size distribution for this class of marine vessels is given in Table 12A.8 [3, 10]. These vessels are predominantly found in

Table 12A.8 Size

Distribution of Ocean-Going Vessels

|

|

Displacement (tonnes)* |

Length |

Anchor Size |

Proportion of Ships (%) |

|

1,500 – 25,000 25,000 – 75,000 75,000 – 100,000 |

1,500 – 35,000 35,000 –

110,000 |

75 – 200 200 – 300 300 – 350 |

2 – 5 5 – 12 12 – 15 |

60 35 5 |

|

† Dead Weight (dwt) = Cargo +

Fuel + Water + others * Displacement = Total Weight = Displacement

has been assumed to be ~ 1.4 ´ dwt |

||||

This section identifies the main hazards from the

subsea gas pipelines. Hazard

identification is based on a literature review of past incidents as well as

HAZID studies (Section 12A.4.2)

conducted for the proposed pipeline. Hazards identified from these studies are then

carried forward for further consideration in the QRA.

12A.4.1

Literature Review

Incident Databases and Pipeline Reports

The Consultants (ERM) have examined incident

databases such as the MHIDAS [11] and the IChemE Accident

Database [12]. Only two pipeline

incidents in offshore

Relevant reports on major subsea pipeline failures

(that caused fatality) by the National Transportation Safety Board have also

been reviewed [13, 14]. A summary of a

few main incidents from these sources are included in the following paragraphs.

On October 23, 1996, in

The incident occurred due to incorrect information on

the location of the gas pipeline that was passed on by the gas company to the

dredging operator. The investigation

report on the incident (by the National Transportation Safety Board) recommended

that all pipelines crossing navigable waterways are accurately located and

marked permanently.

In an incident in the Mississippi River Delta in

1979, four workers drowned attempting to escape a fire that resulted when a crane

barge dropped a mooring spud into an unmarked high pressure natural gas

pipeline.

In July 1987, while working in shallow waters off

A similar accident occurred in October 1989. The menhaden vessel Northumberland struck a

16" gas pipeline in shallow water near

Pipeline Failure Databases

There are a few international failure databases for

gas and liquid transmission pipelines which are useful in identifying potential

hazards and estimating the frequency of loss of containment incidents.

The most comprehensive database on offshore gas

pipeline failures is available in a report published by the UK Health and

Safety Executive entitled 'PARLOC 2001' [6].

The most recent version of this database covers incidents from the 1960s

up to 2000. The information in this

database is based on data obtained from regulatory authorities in the

A similar database on incidents involving offshore

pipelines in the

Table 12A.9 Causes

of Subsea Pipeline Incidents from PARLOC 2001 [6]

|

Main cause |

Detail |

No. of Incidents of Loss of

Containment |

||

|

|

|

Platform Safety Zone(1) |

Subsea Well Safety Zone(2) |

Mid-line |

|

ANCHOR |

Supply Boat |

6 |

- |

- |

|

|

Rig or Construction |

- |

- |

- |

|

|

Other/ Unknown |

0 |

- |

2 |

|

|

Total |

6 |

- |

2 |

|

IMPACT |

Trawl |

- |

- |

6 |

|

|

Dropped Object |

- |

- |

- |

|

|

Wreck |

- |

- |

1 |

|

|

Construction |

1 |

- |

- |

|

|

Other/ Unknown |

- |

- |

1 |

|

|

Total |

1 |

- |

8 |

|

CORROSION |

Internal |

3 |

4 |

7 |

|

|

External |

1 |

- |

2 |

|

|

Unknown |

1 |

- |

2 |

|

|

Total |

5 |

4 |

11 |

|

STRUCTURAL |

Expansion |

- |

- |

- |

|

|

Buckling |

- |

- |

- |

|

|

Total |

- |

- |

- |

|

MATERIAL |

Weld Defect |

2 |

- |

1 |

|

|

Steel Defect |

2 |

1 |

1 |

|

|

Total |

4 |

1 |

2 |

|

NATURAL HAZARD |

Vibration |

- |

- |

- |

|

|

Storm |

- |

- |

- |

|

|

Scour |

- |

- |

- |

|

|

Subsidence |

- |

- |

- |

|

|

Total |

- |

- |

- |

|

FIRE/ EXPLOSION |

Total |

- |

- |

- |

|

CONSTRUCTION |

Total |

- |

- |

- |

|

MAINTENANCE |

Total |

- |

- |

- |

|

OTHERS |

Total |

2 |

1 |

4 |

|

TOTAL |

|

18 |

6 |

27 |

|

(1) Platform safety zone and subsea safety zone

refer to pipelines located within 500m of an offshore platform and subsea

well respectively (2) Mid-line refers to pipelines located

more than 500m from a platform or subsea well. |

||||

Table 12A.10 Causes

of Subsea Pipeline Incidents from US DOT Database [15]

|

Cause of Failure |

Description of Cause |

No. of Incidents |

% of Total Incidents |

Incidents Considered

(1) |

|

|

1. EXTERNAL

FORCE |

25 |

29.8% |

24 |

||

|

Earth Movement |

Subsidence, landslides |

2 |

2.4% |

2 |

|

|

Heavy Rains/Floods |

Washouts, floatation, scouring |

1 |

1.2% |

|

|

|

Third Party |

|

21 |

25.0% |

21 |

|

|

Previously Damaged Pipe |

Where encroachment occurred in the past |

1 |

1.2% |

1 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

2. CORROSION |

45 |

53.6% |

3 |

||

|

External Corrosion |

Failure of coating/CP |

3 |

3.6% |

3 |

|

|

Internal Corrosion |

|

42 |

50.0% |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

3. WELDS

& MATERIALS |

4 |

4.8% |

4 |

||

|

Defective Fabrication Weld |

Welds in branch connections, hot taps, weld-o-lets,

sleeve repairs |

2 |

2.4% |

2 |

|

|

Defective Girth Weld |

|

2 |

2.4% |

2 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

4. EQUIPMENT

& OPERATIONS |

3 |

3.6% |

|

||

|

Equipment Failure |

Malfunction of control or relief equipment, failure

of threaded components, gaskets & seals |

3 |

3.6% |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

5. OTHERS |

7 |

8.3% |

7 |

||

|

Unknown |

|

7 |

8.3% |

7 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

TOTAL |

84 |

100% |

38 |

||

|

1.

Only

these incidents are considered relevant to the proposed pipeline. |

|||||

Incident Records and Protection Measures for Pipelines in

A review of existing and proposed subsea pipelines in

Subsea Pipelines

Existing subsea pipelines in

·

The

28" natural gas pipeline from Yacheng Field, South China Sea (90km south of

·

the

20" dual aviation fuel pipelines

between Sha Chau jetty and

the airport (about 5km length), installed in 1997, are laid in a 2.2 m trench

and provided with sand cover plus rock armour protection. The water depth along the route varies from

4-7 m. There has been no incident of

damage reported;

·

the Airport Authority propose to construct another 5 km submarine aviation fuel pipeline from Sha Chau jetty to the new tank

farm in Tuen Mun. The pipeline will be crossing the

·

the town gas subsea pipelines are

also reported to have no damage record.

These pipelines are laid at a depth of 2 to 3 m below seabed and

protected by engineering backfill materials;

·

the Hongkong Electric Company Limited recently

laid a pipeline from its Lamma Power Station

Extension to Shenzhen LNG Terminal. The

pipeline is jetted to 3 m below seabed and protected with rock armour in high

risk areas near the anchorages and shore approaches; and

·

the recently installed town gas

subsea pipeline from Shenzhen to Tai Po is jetted to 3 m below seabed with

additional rock armour protection in high risk areas.

By comparison, the proposed CAPCO pipeline will be

laid in waters between 2 and 20 m deep.

The pipeline will be provided with 3 m of rock cover except in areas of

shallow water where it will have 1.5 – 5 m of rock/ natural fill cover. These rock cover requirements are based on

water depth (which determines the size of vessels) and marine traffic

volume. The measures proposed are in

line with, or exceed, comparable pipeline installations.

12A.4.2

HAZID Report

A Hazard Identification (HAZID) workshop was held in

September 2009 as part of the risk assessment to identify issues specific to

locality of the pipeline. The worksheets

from this workshop are presented in Table 12A.11.

Table 12A.11 HAZID

Worksheets

|

System: 1. Pipeline |

||||

|

Subsystem: 1. Operational |

||||

|

Hazards/ Keywords |

Description/ Causes |

Consequences |

Safeguards |

Recommendations |

|

1. Internal corrosion |

1. No issue for non corrosive, clean and dry gas |

|

|

|

|

2. External corrosion |

1. Sea-water; corrosive environment |

1. Loss of wall thickness leading to potential leak |

1. Coating system |

|

|

2. Sacrificial anode system |

||||

|

3. Designed for intelligent pigging |

||||

|

3. Pressure cycling |

1. Pipeline pressure will vary with time of day, loads etc |

1. Metal fatigue leading to crack |

1. Design will consider pressure cycles |

|

|

4. Material defect/ construction defect |

|

1. Possible leaks |

1. Quality control during manufacture and construction |

|

|

5. Impact from one pipeline to the other |

1. No issues identified during operation |

|

|

|

|

6. Maintenance |

1. Possible damage to one pipeline during

maintenance/intervention on the second. |

1. Possible damage to pipeline leading to potential leaks |

1. Maintenance procedures: - proper equipment - surveying (GPS positioning) - marker buoys |

|

|

System: 1. Pipeline |

||||

|

Subsystem: 2. External hazards |

||||

|

Hazards/ Keywords |

Description/ Causes |

Consequences |

Safeguards |

Recommendations |

|

1. Anchor Drag |

1. Emergency anchoring for vessel underway due to loss of

steerage, power or control, either due to mechanical problems or due to

collision events. |

1. Possibility of damage to external coating, damage to

pipe requiring remedial action. |

1. Engineered rock protection with respect to vessel

sizes/types. |

1. Periodic survey along the route to be carried out to

ensure integrity of the protection. |

|

2. Drag from anchorage areas under storm conditions. |

2. Potential loss of containment leading to gas release.

Impact on passing vessels and shore population. Vessel involved in the

incidents may sink due to loss of buoyancy cause by the gas bubbling. |

2. Depth of cover. |

||

|

3. Anchoring by vessels outside anchorages. |

3. Disturbance to the rock cover

protection. Possible exposure of the pipe. |

3. Route avoiding anchorage areas. |

||

|

4. Concrete external coating. |

||||

|

5. Heavy wall pipe in shore approaches. |

||||

|

6. Marking marine charts of the pipeline route. |

||||

|

7. Shore population is at least 3km away along the route except near

the shore approach. |

||||

|

2. Anchor Drop |

1. Same as cause 1 & 3 of anchor drag hazard |

1. Same as consequence 1, 2 & 3 of anchor drag hazard

but less severe. |

1. Same as for anchor drag hazard. |

|

|

3. Dropped Object |

1. Loss of cargo |

1. Same as consequence 1, 2 & 3 of anchor drag hazard

but less severe. |

1. Same as safeguards 1, 2, 4, 5, & 7 of anchor drag

hazard. |

|

|

2. Construction activities |

||||

|

4. Dumping |

1. Dumping of construction waste and other bulk materials

outside of designated dumping grounds.

|

1. Minor surface damage. |

1. Same as safeguards 1, 2, 4, 5, & 7 of anchor drag

hazard. |

|

|

5. Grounding |

1. Navigation error, loss of control due to mechanical or

adverse weather. |

1. Same as consequence 1, 2 & 3 of anchor drag

hazard. |

1. Burial depth appropriate to the type of shipping

activities |

|

|

2. Displacement of the pipeline leading to exposure |

2. Comprehensive risk based design has been conducted and

the pipeline alignment minimizes exposure to major shipping lanes. Pipeline is routed through shallow water as far as

possible. |

|||

|

6. Vessel Sinking |

1. Collision, foundering. |

1. Same as consequence 1, 2 & 3 of anchor drag hazard. |

1. Comprehensive risk based design has been conducted and

the pipeline alignment minimizes exposure to major shipping lanes. Pipeline is routed through shallow water as far as

possible. |

|

|

7. Fishing & Trawling |

1. Operation of

trawl board and other fishing/trawl gear. |

1. No damage to the pipeline. |

1. Pipeline is buried below the seabed with rock cover

flush with seabed. |

|

|

8. Dredging |

1. Impact from dredge bucket or drag head. |

1. Same as consequence 1, 2 & 3 of anchor drag hazard

but less severe. |

1. Burial depth appropriate to the type of shipping

activities based on Marine Department and CEDD guidelines. |

|

|

2. Engineered rock protection with respect to vessel

sizes/types. |

||||

|

3. Depth of cover. |

||||

|

4. Marking marine charts of the pipeline route. |

||||

|

5. Concrete external coating. |

||||

|

9. Service crossing or other services in the vicinity |

1. No crossings envisaged |

|

1. Surveys have demonstrated no other services along the

pipeline route |

|

|

System: 1. Pipeline |

||||

|

Subsystem: 3. Natural hazards |

||||

|

Hazards/ Keywords |

Description/ Causes |

Consequences |

Safeguards |

Recommendations |

|

1. Scouring |

1. Current and wave actions |

1. Possible reduction of cover |

1. Alignment is away from areas of high currents |

1. Periodic survey along the route to be carried out to

ensure integrity of the protection. |

|

2. Engineered rock cover |

||||

|

2. Seismic event |

1. Low seismic activity area |

1. No damage |

1. None required |

|

|

3. Subsidence |

1. No issue |

|

|

|

|

System: 1. Pipeline |

||||

|

Subsystem: 4. Construction / future developments |

||||

|

Hazards/ Keywords |

Description/ Causes |

Consequences |

Safeguards |

Recommendations |

|

1. Damage to pipeline during construction of second

pipeline |

1. Damage from construction activities |

1. Damage to pipe and possible loss of containment |

1. Design for appropriate separation distance |

2. Design for second pipeline should be taken into account

during construction of the first. Critical areas such as the shore approach should be

pre-constructed in parallel for the two pipelines. |

|

2. Construction procedures: - proper equipment - surveying (GPS positioning) - marker buoys. |

||||

|

3. Pipeline protection design covers foreseeable marine

activities including dredging and anchoring |

||||

|

2. Reclaimed land over first pipeline |

1. Weight of overburden may lead to subsidence and damage

to first pipeline. |

1. Overstressing of the first pipeline leading to

catastrophic failure |

1. Conservative design taking into account the overburden. |

|

12A.4.3

Hazardous Properties of Natural Gas

The natural gas to be transmitted by the pipeline

predominantly contains methane (85 - 99.5 mol%). It is a flammable gas that is lighter than

air (buoyant). The properties of natural

gas are summarised in Table 12A.12.

Table 12A.12 Properties

of Natural Gas

|

Property |

Natural

Gas |

|

Synonyms State Molecular Weight Density (kg/m3) Flammable Limits (%) Auto-ignition Temperature (°C) |

Methane Gas 16.0 - 18.7 0.55 (at atmospheric conditions) 5 - 15 540 |

12A.4.4

Discussion on Subsea Pipeline Hazards

The incident records highlight the potential for

damage to subsea pipelines from marine activity such as fishing, dredging and

anchoring as well as the potential for the vessel (that caused damage) to

become involved in the fire that follows.

A review of subsea pipeline incidents in Europe and

the

It is noted that the above databases cover a large

proportion of well fluid pipelines where internal corrosion is relevant as

compared to clean natural gas as considered in this study.

Most existing pipelines in

A brief description of the main causes of failure of

a subsea pipeline is included in the following paragraphs.

External Impacts

Anchor drop/drag is the dominant cause of potential

failure or damage to a subsea pipeline.

This occurs when a ship anchor is dropped inadvertently across the

pipeline. The type of damage that could

be caused will vary depending on the size of anchor and other factors such as

pipeline protection.

Anchor Drop

The decision for a mariner when to drop an anchor depends

on the particular circumstances and the proximity of the pipeline route to the

flow of marine traffic, port/harbour areas and designated anchorage

locations. In fairways, traffic will

normally be underway where the necessity to drop anchor is expected to be

low. Consistent with normal practice,

the pipeline route will be identified on nautical charts. The mariner is then provided with the

necessary information to avoid anchoring where the pipeline could be

damaged.

Emergency situations may arise such as machinery

failure or collision thereby limiting the choice where to drop anchor. Such a decision will, as part of a mariner’s

responsibility, be influenced by the particular circumstances and the pipeline route

delineated on the navigation chart.

Although it is expected that vessels should be aware

of all subsea installations (including gas pipelines) since these are marked on

the admiralty nautical charts, erroneous dropping of anchor (i.e. error in

position at the time of deployment) are known to occur.

Anchor Drag

Anchor drag occurs due to poor holding ground or

adverse environmental conditions affecting the holding power of the

anchor. The drag distance depends on

properties of the seabed soil, the mass of ship and anchor and the speed of the

vessel. If there is a subsea pipeline

along the anchor drag path, anchor dragging onto the pipeline may result in

localised buckling or denting of the pipeline, or over-stressing from bending

if the tension on the anchor is sufficient to laterally displace the

pipeline. A dragged anchor may also hook

onto a pipeline during retrieval causing damage as a result of lifting the

pipeline.

Vessel Sinking

Vessel sinking in the vicinity of the pipeline may

cause damage to the pipeline resulting in loss of containment. Vessel sinking will depend on the intensity

of marine activity in a given area. For

the years 1990 to 2007, there were 492 incidents of vessel sinking in

Dropped Objects

Objects other than anchors may be dropped from

vessels passing over the pipeline or vessels operating in the vicinity. The dropped objects may include shipping

containers, construction/maintenance equipment, etc. The pipelines will be lowered to at least 1 m

below seabed and protected by rock armour.

Given the likely sizes of dropped objects and the level of pipeline

protection provided, loss of containment due to dropped objects is not

considered to be a significant contributor to the risk. Such events will in any case be included in

the historical pipeline failure data for external impact used in this

study.

If any future construction work is conducted in the

vicinity of the pipeline, procedures will be developed to safeguard the

pipeline during the construction activities.

Aircraft Crash

The proposed pipeline route does not lie close to Chek Lap Kok or

Fishing Activity

Based on the BMT report [3], there is fishing

activity along the proposed pipeline route.

Many of the techniques involve towing of a variety of equipment along

the seabed. Pipeline damage from fishing

gear can occur due to impact, snagging of nets or trawl door on the pipeline or

a "pull over" sequence. Impact

loads mainly cause damage to the coating whilst pull over situations can cause

much higher loads, which could lead to damage of the steel pipeline

itself.

The vessels of concern are stern trawlers with

lengths up to 30 m. Considering the size

and weight of trawl gear and since the pipeline will be lowered to at least 1 m

below seabed and protected by rock armour for the entire route, pipeline damage

due to trawling activities are not possible and are not considered further.

Dredging and Construction Activities

Dredging vessels could cause damage due to dredging

operations involving cutting heads. They

could also cause damage to the pipeline by anchoring.

It is assumed that dredging operations will be

closely monitored and controlled and therefore there is negligible potential

for pipeline damage due to dredging.

Spontaneous Failures

Corrosion

Corrosion is one of the main contributors to pipeline

failures. Corrosion is attributed mainly

to the environment in which they are installed (external) and the substances

they carry (internal).

The proposed pipeline will be protected against

external corrosion by sacrificial anodes in addition to an anti-corrosion

coating. However, ineffective corrosion

protection due to a failure or breakdown of the protection system could cause

external corrosion resulting in general or local loss of wall thickness leading

to pipeline failure.

Historically, internal corrosion is a greater cause

of pipeline failure compared to external corrosion. However, the proposed pipeline will transport

gas that does not contain components that induce corrosion such as

water/moisture, carbon dioxide, hydrogen sulphide, etc. This will largely reduce the chance of

internal corrosion.

Despite these considerations, loss of containment due

to corrosion (both internal and external) remains a possibility and is included

in the analysis.

Mechanical Failure

Mechanical failure of the pipeline could occur for

various reasons, including material defect, weld failure, etc. Stringent procedures for pipeline material

procurement, welding and hydrotesting should largely mitigate against these hazards. In any case, it remains a credible scenario

and is included in the frequency data.

Natural Hazards

Natural hazards such as subsidence, earthquake and

typhoon may cause varying degrees of damage to pipelines.

Soft soil can sometimes suffer from localised

liquefaction which can result in pipelines floating out of their trenches. The pipeline will be designed to withstand

such loads, based on detailed seabed investigations.

Environmental loads (currents and waves) on the

pipeline during the construction phase can compromise the lateral and vertical

on-bottom stability of the pipeline on the seabed. This problem becomes more acute in shallower

waters (near the shore) where the pipeline attracts a higher level of

environmental loads. The pipeline will

be designed to withstand these environmental loads. Once it is lowered below the seabed, it would

not be exposed directly to 100 year return wave loads.

Based on the above considerations, it is considered

that there is no disproportionate risk to the pipeline from natural

hazards. These causes of failure are in

any case included in the generic failure rates derived from historical

incidents, as used in this study.

12A.5.1

Overview

This section presents the base failure frequency data

for the hazards identified in Section 12A.4. The approach to frequency analysis is based

on the application of worldwide historical data for similar systems, modified

suitably to reflect local factors such as proximity of the pipeline to busy

shipping channels and anchorages.

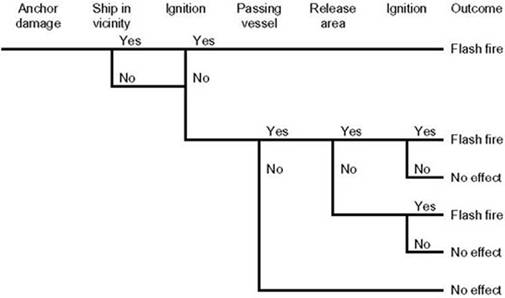

Event tree analysis was used to determine the

probabilities of various hazard outcomes (such as flash fire) occurring,

following a release.

12A.5.2

Historical Data

The international database that is most comprehensive

in its coverage of subsea pipelines is PARLOC 2001 [6]. The most recent version of this database

which was used in this study covers incidents from the 1960s until 2000. Incidents recorded in the database have been

classified according to several categories, including:

·

Failure

location, i.e. risers, pipelines within 500 m of an offshore platform,

pipelines within 500 m of a subsea well and mid-line (pipelines located more

than 500 m from a platform or a subsea well).

Failure data pertaining to risers is not relevant to this study and has

therefore been excluded;

·

Pipeline

contents. The database includes both oil

and gas pipelines. Where the contents in

the pipeline have an impact on failure rate, such as corrosion, only incidents

pertaining to gas pipelines are considered; and

·

Pipeline

type, i.e. steel pipelines (both pipe body and fittings) and flexible

lines. Only failures involving the pipe

body of steel pipelines are considered here.

A breakdown of the incidents recorded in PARLOC 2001

by failure location is shown in Table

12A.13. The number of incidents of

loss of containment that have occurred within 500 m of a platform or a subsea

well is almost equal to the number of incidents that have occurred away from it

(i.e. mid-line). The higher failure rate

in the vicinity of an offshore installation (one to two orders of magnitude

higher than mid-line) is due to the effect of increased ship/barge movements in

the vicinity and the potential for anchor damage as a result.

The proximity of some sections of the proposed

pipeline route to high marine traffic environments could be regarded as similar

to the environment in the vicinity of the platform safety zone although it is

not strictly comparable.

Table 12A.13 Failure

Rate Based on PARLOC 2001 [6]

|

Region of Pipeline |

Operating Experience |

No. of Incidents |

Failure Rate |

|

Mid-line |

297,565 km-years |

27 |

9.1´10-5 /km/year |

|

Platform safety zone |

16,776 years |

18 |

1.1´10-3 /year |

|

Subsea well safety zone |

2,586 years |

6 |

2.3´10-3 /year |

|

Total |

307,246 km-years* |

51 |

1.66´10-4 /km/year |

* The number of years in the case of platform and

subsea well safety zone is multiplied by 0.5km of safety zone to obtain

corresponding km-years

The main causes of pipeline failure are summarised in

Table 12A.14, based on the causes identified in PARLOC 2001. As discussed earlier,

anchor/impact and internal corrosion are the main contributors to pipeline

failure.

Table 12A.14 Main

Contributors to Subsea Pipeline Failure (PARLOC 2001)

|

Cause |

Platform Safety Zone |

Subsea Well Safety Zone |

Mid-line |

Total |

|

Anchor/Impact |

7 (39%) |

- |

10 (37%) |

17 (33%) |

|

Internal corrosion |

3 (17%) |

4 (67%) |

7 (26%) |

14 (27%) |

|

Corrosion -others |

2 (11%) |

- |

4 (15%) |

6 (12%) |

|

Material defect |

4 (22%) |

1 (17%) |

2 (7%) |

7 (14%) |

|

Others |

2 (11%) |

1 (17%) |

4 (15%) |

7 (14%) |

|

Total |

18 |

6 |

27 |

51 |

Analysis of Failure Causes

The failure frequency derived from the PARLOC 2001

data is further filtered to take into account the local conditions in

Corrosion

and Material Defect

Based on experience in

Failures due to defects in materials and welds are

also expected to be lower than implied by the historical record due to

technological improvements. The database

for PARLOC 2001 dates back to the 1960s; there have been significant

improvements in pipe material and welding over the last 10 to 20 years. An 80% reduction is therefore assumed for all

forms of corrosion and material defects.

Taking the mid-line data as the most representative

for the proposed pipeline, the failure rate is therefore derived as 13

incidents in 297,565 km-years with 80% reduction, giving 8.7´10-6

/km/year.

The PARLOC 96 report [17] provides a

breakdown of loss of containment incidents due to corrosion and material defect

for gas pipelines greater than 5km in length.

The failure rate for such pipelines is lower at 5.9´10-6 /km/year (0.7 failures in

119,182 km-years; the km-years are lower because only gas pipelines are

considered). This value is considered

more appropriate for the proposed pipeline.

Unfortunately, a more current value could not be extracted from PARLOC

2001 due to a difference in presentation format of the data. However, a downward trend in failure

frequencies is to be expected as technology improves and so 5.9´10-6

/km/year is considered to be reasonable.

Incorporating an 80% reduction again gives a corrosion/defect frequency

of 1.18´10-6

/km/year.

Anchoring/Impact Incidents

There is a significant difference in the failure rate

due to anchor/impact incidents for pipelines within 500m of an offshore

platform (8.3 ´ 10-4/ km/ year) as compared to mid-line

(3.4´10-5 /km/year). Further breakdown of incidents based on

pipeline diameter is given in Table

12A.15.

Table 12A.15 Frequency

of Loss of Containment Incidents due to Anchor/Impact- Breakdown by Pipe

Diameter & Location

|

|

Frequency (per km per

year) |

|||

|

Location |

<10" diameter |

10 to 16" diameter |

18 to 24" diameter |

24 to 40" diameter |

|

Mid-line |

1.53´10-4 |

2.26´10-5 |

1.76´10-5 |

1.37´10-5 |

|

Safety zone |

6.68´10-4 |

1.94´10-3 |

4.24´10-4 |

8.6´10-4 |

It is seen from the above that the failure rate (for mid-line)

for larger diameter pipelines is lower by an order of magnitude in comparison

to smaller diameter pipelines.

As discussed previously, it is considered that the

likelihood of pipeline damage due to anchor/impact incidents may be related to

the level of marine activity (this is taken to be a combination of marine

traffic and anchoring activity). The

frequency of pipeline failure due to these causes has therefore been derived as

a function of three levels of marine activity: high, medium and low. Frequency values are based on the large

diameters pipes of 24-40” as given in Table

12A.15 since these are the most relevant to the proposed CAPCO

pipeline.

For locations with high marine activity, a

frequency of 8.6´10-4 /km/year

is adopted. For low marine activity, 1.37´10-5 /km/year is used. An intermediate value of 10-4

/km/year is also applied to locations with medium levels of marine

activity. This is discussed further in Section 12A.5.3 where alternative

calculations based on emergency anchor deployment frequency are also presented

for comparison.

These failure frequencies from PARLOC assume minimal

protection for the pipeline. The

proposed CAPCO pipeline will be provided with rock armour protection over its

entire length. To allow for this, the

failure frequencies are reduced by appropriate factors as discussed in Section 12A.5.4.

Other Causes

“Other” causes include blockages, procedural errors,

pressure surges etc. As with corrosion,

improvements in technology and operating practices are expected to reduce this

significantly and so a general 90% reduction is assumed for failures due to

other causes. This gives a frequency of

1.34´10-6/km/year

(4 cases in 297,565 km-years with 90% reduction).

12A.5.3

Alternate Approach to Anchor Damage

Frequency

While international data is commonly applied to infer

failure rates for

Frequency of Anchor Drop

Emergency Conditions

Vessels may drop anchor due to emergency conditions

such as fog, storm, or due to collisions or machinery failure. The likelihood of anchoring due to adverse weather

conditions is expected to be low especially for the larger vessels who will

determine whether dropping an anchor is the safest option. Furthermore, knowledge of vessel position

from onboard navigation systems should prevent inadvertent dropping of an

anchor onto a pipeline delineated on the navigation chart.

To

estimate the frequency of emergency anchoring, data from the Marine Department

of Hong Kong [5] is used. The

distribution of incidents of all types (Figure

12A.4) shows that most incidents are concentrated in the harbour regions

near Yau Ma Tei, Tsing Yi and Tuen Mun. The region near

the proposed pipeline indicates low incident rates, although some areas of

Average

values of 0.3 appearing in Figure 12A.4

clearly refers to a single incident that occurred during

the 3-year period from 2001 to 2003. The

size of each cell in Figure 12A.4 is

one nautical mile, or approximately

1.852 ´ 1.852 = 3.4 km2. A value of 0.3 refers then to an incident

frequency rate of 0.3/3.4 @ 0.1 /km2/year. This incident rate is taken to be appropriate

for sections of the pipeline away from the busy

The incident rate for

For comparison, the total number of incidents from

1990-2008 in the 1830 km2 area of Hong Kong SAR waters was 6491

[16]. This gives a territory average of

0.19 /km2/year.

Figure 12A.4 Average

Annual Incident Distribution (2001-2003)

|

|

The distribution by types of incidents (Figure 12A.5) shows that most incidents

are collisions or contact. Not all

incidents will result in an anchor drop.

Most collisions, for example, are not serious. It is assumed therefore that only 10% of

incidents will result in an emergency anchor drop.

Once the anchor is dropped, it may fall directly on

the pipeline causing damage. A greater

concern is the possibility of an anchor being dragged across the seabed and

into the pipeline. In an emergency

situation such as mechanical failure, it is possible that the vessel is still

moving when the anchor is deployed.

Since anchors can be dragged significant distances, the resulting

pipeline contact frequencies tend to be higher compared to a simple anchor

drop. In most instances, however, the

ship master’s first action will be to reduce speed to near stationary and then

drop anchor if necessary. For the purpose

of this analysis, it was assumed that 90% of ships drop anchor at near rest (1

knot), while the other 10% drop anchor at 4 knots due to mechanical failure and

the uncontrolled advance of the vessel.

Figure 12A.5 Distribution of Incident Types

(1990-2008)

|

|

The efficiency of an anchor is defined according to

its holding capacity:

Holding capacity = anchor

weight ´ efficiency

The efficiencies for different classes of anchor [19]

are given in Table 12A.16. It is believed that types E and F are common

on large commercial vessels.

Table 12A.16 Anchor

Efficiency

|

Class |

Efficiency |

|

A |

33-55 |

|

B |

17-25 |

|

C |

14-26 |

|

D |

8-15 |

|

E |

8-11 |

|

F |

4-6 |

|

G |

<6 |

This definition can be used to calculate the drag

distance. The work done in dragging an

anchor through some distance must be equal to the change in kinetic energy in

bringing the ship to rest.

Anchors are designed to penetrate into the seabed for

maximum holding capacity. As an anchor

is dragged across the seabed, it will begin to penetrate into the mud; the

softer the soil, the greater the penetration.

Maximum holding capacity is only reached once the maximum penetration

depth has been reached i.e. the efficiency is a function of penetration

depth. As a conservative approach, the

lowest efficiency anchor, type E, is assumed for the calculations. The efficiency is halved again to allow for

the varying restraining force with depth.

The efficiency is therefore assumed to be 2.

Table 12A.17 gives some drag distances resulting from

these calculations. It can be seen that

most vessels will drag an anchor for less than about 20m. Ocean-going vessels can drag an anchor over

significantly greater distances due to the larger mass and hence kinetic energy

of the ship. This class of ship is

subdivided into different sizes to reflect the distribution of ships expected

along the proposed pipeline route (see Table

12A.8). A 150,000 tonne ship is the

largest of ships visiting

Table 12A.17 Drag

Distances

|

Class |

(dwt) |

Displacement (tonnes) |

|

Anchor |

Drag Distance (m) |

|

Fishing vessel Rivertrade

coastal vessels Ocean-going vessels Fast Launches Fast ferries Other |

1,500 –

25,000 25,000 –

75,000 75,000 –

100,000 |

400 1,500 1,500 –

35,000 35,000 –

110,000 110,000 –

150,000 150 150 200 |

(60%) (35%) (5%) |

1 2 2 – 5 5 - 12 12 - 15 0.1 0.5 0.2 |

7 13 13 – 118 118 – 154 154 – 168 25 5 17 |

The frequency of anchor drag impact can then be

calculated as:

Impact freq =

incident

freq (/year/km2) ´ probability

of anchor drop ´ drag

distance/1000 (1)

where the drag distance is in metres. This gives an impact frequency per km of

pipeline per year. If an impact occurs,

the damage may not be severe enough to cause containment failure. Based on PARLOC 2001, approximately 22% of

anchor /impact incidents result in containment failure when considering all

pipe diameters. Larger pipes, however,

fail three times less often. This

suggests that 7% of incidents would result in a loss of containment.

This approach was applied to each section of the

pipeline and to each class of vessel.

The marine traffic incident rate was assumed to apply equally to all

classes of vessel.

The hydrographic survey [7]

identifies seabed conditions as very soft clay.

Under these conditions, significant anchor penetration can occur

[19]. For example, a 15 tonne anchor can

penetrate to 17m, and a 2 tonne anchor can penetrate to 9m. These data apply to high efficiency anchors

and less penetration is to be expected for the commonly used types E and F, but

nevertheless, it is likely that a wide range of anchors sizes will be able to

achieve 3m penetration during emergency anchoring scenarios and hence may

interact with the proposed pipeline.

MARAD Study

An alternative to using the incident frequency from Figure 12A.4 is to use data from the

MARAD study [18] which reported that the frequency of collisions in

The results from this analysis are compared in Figure 12A.6. Also shown are the loss of containment

frequencies obtained from PARLOC 2001 for the platform safety zone and mid-line. These are assumed to be representative of

areas of high and low marine activity respectively. It can be seen that there is some spread in

the predictions. The platform safety

zone and mid-line frequencies differ by almost two orders of magnitude but

effectively bound most of the other predictions.

Figure 12A.6 Anchor

Damage Frequency Based on Marine Incidents

The calculations are broadly consistent with failure

frequencies from PARLOC 2001. The frequency

obtained from PARLOC 2001 for the mid-line is appropriate for regions of low

marine vessel volume. The platform

safety zone frequency is regarded as appropriate for the failure frequency in

locations of high marine traffic. Some

sections have intermediate levels of marine activity and so a frequency of 10-4

per km-year is adopted for these sections.

Based on the above considerations, the failure

frequencies due to anchor impact used in this study are as summarized in Table 12A.18. A low frequency was assigned to the Black

Point approach since no vessel movements were observed in this area from the

marine radar tracks.

Table 12A.18 Anchor

Damage Frequencies used in this Study

|

Pipeline

section |

Frequency |

Comment |

|

Boundary Section |

1´10-4 |

Medium marine traffic |

|

|

8.6´10-4 |

High marine traffic |

|

Black Point West |

1´10-4 |

Medium marine traffic |

|

Black Point Approach |

1.37´10-5 |

Low marine traffic |

12A.5.4

Pipeline Protection Factors

Many pipelines are trenched to protect them from

trawling damage. In the pipeline

database in PARLOC 2001, 57% by length of all lines have some degree of

protection, either trenching (lowering) or burial (covering) over part or all

of their length. Considering large and

small diameter lines, the proportion of lines with some degree of protection

are 59% by length for lines <16" diameter and 68% for larger diameter

lines. It is, however, concluded in the

PARLOC report that there have been insufficient incidents to determine a clear

relationship between failure rate and the degree of protection.

The loss of containment frequencies

given in Table 12A.18 assume

minimal protection since they are based on the PARLOC data. The proposed CAPCO pipeline has rock armour

protection specified for its whole length.

To allow for this, protection factors were applied. Based on the classes of marine vessel found

along the proposed route (Table 12A.2),

most classes of ship have anchors below 2 tonnes in weight. Only ocean-going vessels have anchors up to

15 tonnes. The rock armour protection

along the route is designed to protect against either 3 – 5 tonne anchors

(trench types 1 and 2) or 19 tonne anchors (trench type 3). The analysis therefore assigns protection

factors for the rock armour and makes a distinction between ocean-going vessels

that have large anchors and other types of vessel which have smaller

anchors.

Trench types 1 and 2 were assumed to provide

99%protection for anchors smaller than 2 tonnes. These trench types should also offer some

protection against larger anchors. For

ocean-going vessels, 60% of them have anchors below about 5 tonnes (Table 12A.8) and so trench type 1 should

offer reasonable protection against these vessels. 50% protection was assumed for ocean-going

vessels. For simplicity, trench type 2 was

treated the same way as type 1 and 50% protection was assumed for large

anchors. This is a little conservative

since trench type 2 is designed to protect anchors up to 5 tonnes.

Trench type 3 (deigned to protect against 19 tonne

anchors) was assumed to provide 99% protection for anchors greater than 2

tonnes, and greater protection of 99.9% for small anchors below 2 tonnes.

12A.5.5

Summary of Failure Frequencies for the

Proposed CAPCO Pipeline

Based on the above discussions, the

failure frequencies used in this study are as summarized in Table 12A.19.

The failure frequencies specified in Table 12A.19 will apply to each of the

two pipelines.

Table 12A.19 Summary

of Failure Frequencies used in this Study

|

Pipeline

section |

Trench type |

Corrosion /defects (/km/year) |

Anchor/Impact |

Others /km/year |

Total* /km/year |

||

|

Frequency (/km/year) |

Protection factor (%) |

||||||

|

anchor<2 |

Anchor>2 |

||||||

|

Boundary Section |

2 |

1.18´10-6 |

1´10-4 |

99 |

50 |

1.34´10-6 |

3.5´10-6 |

|

|

3 |

1.18´10-6 |

8.6´10-4 |

99.9 |

99 |

1.34´10-6 |

4.1´10-6 |

|

Black Point West |

2 |

1.18´10-6 |

1´10-4 |

99 |

50 |

1.34´10-6 |

3.5´10-6 |

|

Black Point Approach |

1 |

1.18´10-6 |

1.37´10-5 |

99 |

50 |

1.34´10-6 |

2.7´10-6 |

* The calculation of total failure

frequency takes into account the size distribution of ships (based on 2011

marine traffic) and the protection factors for anchors

The outcome of a hazard can be predicted using event tree

analysis to investigate the way initiating events could develop. This stage of the analysis involves

development of the release cases into discrete hazardous outcomes. The following factors are considered:

·

Failure

cause;

·

Hole

size;

·

Vessel

position and type; and

·

Ignition

probability.

The probabilities used in the event trees are

discussed below.

Failure Cause

Failures due to corrosion and other events are

considered separately from failures caused by anchor impact. This is because the hole

size distribution is different in each case, as described below. Also, in the event of failure due to anchor

impact, the probability of vessel presence is assumed to be higher, as

discussed later.

Hole Size Distribution

The data on hole size

distribution in PARLOC 2001 is summarised in Table 12A.20.

This data on hole size

distribution is clearly limited, particularly for large diameter

pipelines. One approach is to compare

this distribution with that for onshore pipelines, which include a much larger

database of operating data and failure data.

For example, the US Gas database [15] is based on 5 million pipeline

km-years of operating data as compared to 300,000 km-years in the PARLOC study.

Table 12A.20 Hole Size Distribution from PARLOC 2001

|

Pipeline size |

|

Hole size (mm) |

||

|

Location |

0 to 20mm |

20 to 80mm |

>80mm |

|

|

2 to 9" |

Safety zone Mid

line |

6 14 |

3 (1 rupture) 4 (2 ruptures) |

2 1 (1 rupture) |

|

10 to 16" |

Safety zone Mid

line |

1 1 |

1 |

4 (3 ruptures) 3 |

|

>16" |

Safety zone Mid

line |

1 2 |

|

2 (2 ruptures) |

|

Total |

|

25 (55%) |

8 (18%) |

12 (27%) |

|

|

||||

An analysis of hole size distribution for onshore pipelines

as given in the US Gas [15] and European Gas Pipelines databases [20] provides

a hole size distribution as given in Table 12A.21.

Table 12A.21 Hole Size Distribution Adopted for Corrosion and Other

Failures

|

Category |

Hole Size |

Proportion |

|

Rupture (Half

Bore) |

22" or

558mm |

5% |

|

Puncture |

4" or

100mm |

15% |

|

Hole |

2" or 50mm |

30% |

|

Leak |

<25mm |

50% |

The above distribution is largely similar to the distribution

derived in the PARLOC report [6]. The

only difference is the consideration of a small percentage of ruptures. It is a matter of debate whether ruptures

could indeed occur although ruptures extending over several metres are reported

in the various failure databases.

In this study, it is proposed that the hole size distribution given in Table 12A.21 be adopted for failures caused by corrosion and

‘other’ failures (including material/weld defect). In the case of failures caused by anchor

damage, the hole sizes are expected to be larger. The distribution given in Table 12A.22 is adopted.

Table 12A.22 Hole Size Distribution for Anchor Impact

|

Category |

Hole Size |

Proportion |

|

Rupture (Full Bore) |

Full bore |

10% |

|

Major |

22" or

558mm (half bore) |

20% |

|

Minor |

4" or 100mm |

70% |

Vessel Position

In the case of failures due to corrosion/other

events, the probability of a vessel being affected by the leak is calculated based

on the traffic volume and the size of the flammable cloud. Dispersion modelling using PHAST [21] is used

to obtain the size of the flammable cloud for each hole

size scenario and four weather scenarios covering atmospheric stability classes

B, D and F. Once the cloud size is

known, the probability that a passing marine vessel will travel through this

area within a given time can be calculated.

A time period of 30 minutes is used since it is assumed that if a leak

occurs, warnings will be issued to all shipping within 30 minutes. Further details on the dispersion modelling

are given in Section 12A.6.

In the case of failures due to anchor impact, the

following two scenarios are considered:

·

“Vessels

in vicinity” - the vessel that caused damage to the pipeline (due to anchoring)

is still in the vicinity of the incident zone.

The probability of this is assumed to be 0.3; and

·

“Passing

vessels” - ships approach or pass the scene of the incident following a

failure. In this case, the probability

of a vessel passing through the plume is calculated using the same method as

for a corrosion failure; i.e. based on cloud size and traffic volume.

Event trees showing these scenarios are given in Figures 12A.7 and 12A.8. If a vessel passes

through the flammable gas cloud, a distinction is further made between vessels

passing directly over the release area and vessels passing through other parts

of the cloud. This is discussed further

in the following section.

Figure 12A.7 Event

Tree for External Damage from Anchors

Figure 12A.8 Event

Tree for Spontaneous Failures

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

It is assumed that at most, only one vessel will be

affected by a pipeline failure. Once the

flammable plume is ignited, the resulting fire will be visible and other ships

will naturally avoid the area.

Vessel Type

The categorisation of vessel types follows those

identified from the radar tracks (Table

12A.2), namely:

·

Fishing

vessels and small crafts;

·

Rivertrade coastal vessels;

·

Ocean-going

vessels;

·

Fast

Launches;

·

Fast

ferries;

·

‘Others’

(assumed to be small vessels)

The relative proportion of the different

vessel types will vary along the pipeline route, as indicated in Table 12A.4.

Ignition Probability

Ignition of the release is expected only

from passing ships or ships in the vicinity.

Ignition probabilities derived from offshore pipeline releases in the

vicinity of an offshore platform are given in Table 12A.23 [22]. Similar

values are adopted in this study, as given in Table 12A.24.

Table 12A.23 Pipeline

Hydrocarbon Release Ignition Probability in Platform Vicinity [23]

|

Typical

Ignition Probability (integrated platform) |

|||

|

Location of release |

Massive gas release

(>20 kg/s) |

Major gas release |

Minor gas release(<2

kg/s) |

|

Riser above sea* |

0.168 |

0.026 |

0.005 |

|

Subsea |

0.443 |

0.13 |

0.043 |

|

Typical

Ignition Probability (bridge linked platform) |

|||

|

Location of release |

Massive gas release

(>20 kg/s) |

Major gas release (2-20 kg/s) |

Minor gas release (<2 kg/s) |

|

Riser above sea* |

0.078 |

0.013 |

0.002 |

|

Subsea |

0.14 |

0.051 |

0.002 |

|

|

|||

* 'Riser

above sea' refers to pipeline riser portion that is above sea level

Table 12A.24 Ignition

Probabilities used in Current Study

|

Release Case |

Ignition Probability |

|

|

|

Passing Vessels (1) |

Vessels in Vicinity

(2) |

|

<25mm |

0.01 |

n/a |

|

50mm |

0.05 |

n/a |

|

100mm |

0.1 |

0.15 |

|

Half bore |

0.2 |

0.3 |

|

Full bore |

0.3 |

0.4 |

|

1.

Values

applied to passing vessels for all types of incidents, i.e. corrosion, others

and anchor impact. 2.

Values

applied only to scenarios where the vessel causing pipeline damage due to

anchor impact is still in the vicinity. |

||

12A.5.7

Second Phase Construction Activities

The second pipeline may be constructed concurrently

with the first, or two years later in 2014.

From a risk perspective, construction of the pipelines at different times

may present an increase in risk due to construction activities from the second

pipeline impacting on the first operational pipeline.

The project has taken this into consideration with

the following safeguards:

·

The

two pipelines will be located 100 m apart;

·

The

pipelines are planned to run parallel without any crossing points and without

crossing any other existing pipelines;

·

Strict

procedures for construction activities involving surveys, confirmation of

location using Global Positioning Systems and the demarcation of alignment

using marker buoys;

·

The

pipelines are protected against damage from dredging by rock protection along

their full length; and

·

Design

for the second pipeline will be taken into account during construction of the

first pipeline. Critical areas, such as

the shore approaches will be pre-constructed in parallel for the two pipelines

as far as practicable.

The Gas Production & Supply Code of Practice [24]

provides a practical guidance in respect of the requirements of the Gas Safety

Ordinance Cap 51 and the Gas Safety (Gas Supply) Regulations. Article 23A of these regulations requires

that:

·

No

person shall carry out, or permit to be carried out, any works in the vicinity

of a gas pipe unless he or the person carrying out the works has before

commencing the works, taken all reasonable steps to ascertain the location and

position of the gas pipe; and

·

A

person who carries out, or who permits to be carried out, any works in the

vicinity of a gas pipe shall ensure that all reasonable measures are taken to

protect the gas pipe from damage arising out of the works that would be likely

to prejudice safety.

Work, ‘in the

vicinity’ is defined according to Table

12A.25 and these guidelines apply to both onshore and subsea

pipelines. Although many of the

activities listed are not directly relevant to the proposed CAPCO pipeline, Table 12A.25 serves to indicate typical

effects distances for different types of work and when special precautions are

warranted. A separation distance of 100m

is very significant compared to distances listed in Table 12A.25. This, combined with the strict procedures that will be

followed and the pipeline protection provided, suggests that the likelihood of damage

to the first operational pipeline from construction activities during phase 2

will be very low. This is therefore not

considered further in this study.

Table 12A.25 Works

in the Vicinity of Gas Pipes

|

Type of Work |

Distance |

|

Trench or other

excavation up to 1.5m in depth in stable ground |

10m |

|

Trench or other

excavation over 1.5m and up to 5m in depth |

15m |

|

Trench or other

excavation in stable ground over 5m in depth |

20m |

|

Welding or hot works

near exposed gas pipes or above ground installations |

10m |

|

Piling, percussion moling

or pipe bursting |

15m |

|

Works near high pressure pipelines |

20m |

|

Ground investigation and any kind of

drilling or core sampling |

30m |

|

Use of explosives |

60m |

The construction activities may also increase risk by

increasing the population within the vicinity of the operational pipeline. Any incident affecting the operational pipeline

may impact on the construction workers and lead to a higher number of

fatalities.

The hazard effects exceed 100m only for the half bore

rupture case in weather condition 7D (refer to Consequence Analysis). This scenario has a hazard range of 115

m. Geometric considerations (Figure 12A.9) imply that a leak from a

section of pipeline just 114m long has the potential to reach the workers 100 m

away.

Figure 12A.9 Construction

Workers’ Proximity to Pipeline

|

|

An incident at the operating pipeline may be caused

by internal failure or external impact.

Internal Failure

The failure frequency (Table 12A.19) for internal failure is

2.52´10-6 /km/year ([1]) . The

frequency of events from the operational pipeline impacting on construction

workers at the second pipeline may be estimated from:

![]() /year

/year

Where the factor of 114/1000 arises from the

geometric considerations and the fact that an incident must occur within a 114m

length section of the pipeline to affect the workers. 0.695 refers to the probability of weather

category 7D and a factor of 1/6 is applied to approximate the probability of

the wind blowing towards the construction workers. The factor of 0.05 corresponds to the

probability of the leak size being half bore rupture for internal failures and

0.2 corresponds to the ignition probability for this sized leak.

External Impact

The highest frequency (ie.

![]() /year

/year

Where the probability of half bore rupture is taken

to be 0.2 for external damage and the factor of (1-0.3´0.3) represents the probability that the

vessel causing the damage did not itself ignite the release (0.3 for the vessel

that caused the damage is still present and 0.3 for the ignition probability). Other terms are the same as in the internal

failure case.

Combining the internal and external

failure scenarios gives a total frequency of 1.09´10-9 per year that the

construction workers will be affected by an incident at the operational